“Rules are the rules…” by ncorva, Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License

Much like fantasy novel writing, Dungeon Mastering requires a slew of creative skills to set a scene, develop a plot, and create riveting contention that propels the story onward. However, contrary to writing, a Dungeon Master has the unique benefit of being only one of many voices telling the story, as players develop the story just as much as Dungeon Masters. How can a Dungeon Master ensure they are shaping a cohesive story instead of simply facilitating a game? In this article, I’ve collected advice from famous authors and storytelling experts to guide narrative creation and facilitate player interaction. Let us attain useful game-development tips from these Masters of Fantasy.

Because we are working within the framework of Dungeons and Dragons 5th edition, the tips I have compiled fall into the following categories: Beginning Your Campaign, Developing Meaningful Conflicts, and Including Riveting Details.

Beginning Your Campaign

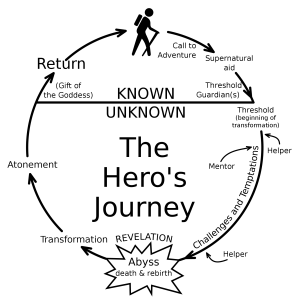

Whether the medium is television, video games, plays, books, or roleplaying games, stories tend to follow a tried-and-true story circle. Influenced by psychologist Carl Jung’s opinions on myths, famous American Professor of Literature Joseph Campbell developed a 17-step template for story-writing, the Hero’s Journey. For our purposes, let’s focus on the first bit of the journey and explore its relation to the dawning of your campaign.

The Call to Adventure typically happens prior to actually playing, where backstories and characters are told about rather than shown, which I would argue is unfortunate. It’s not uncommon to feel awkward in a first session where a Dungeon Master does not quite know how to start the campaign and reverts to the “You all meet in a tavern” scenario. Perhaps following an abbreviated version of the Hero’s Journey in the first session or session zero will facilitate a roleplay-rich and memorable introduction to your campaign.

As a Dungeon Master, ask your players well in advance for backstories and flaws, whether they be in-depth or simple. What we’ll establish below is that you need not start your campaign immediately at a point of conflict. Use the Hero’s Journey to develop non-player characters, familiarize your players with each others’ backstories, and establish motivation for adventuring, all within the first session.

Call to Adventure

Each of your characters would benefit from their own Call to Adventure, purposefully played out individually. Using the Hero’s Journey, you would start your story in a scene of normalcy for each character. They are all simply going about their business in the same vicinity, whether they are acquainted with each other or not. One by one, they will witness or receive information that carries them to a point where they must decide to jump out of their routines and into the story.

The call to adventure could involve one, a few, or many of your players seeking out experts (each other) to join them on their quest; a player could witness some sort of injustice that provokes them to meddle; a character could have a very personal connection to the call, such as a family member being kidnapped or a rival inciting them to act; or perhaps each player has their own relationship to the same non-player character that brings them together in various ways.

Perhaps two of your players have come to a town in search of a few magical items and observe a scuffle involving another player. After these players resolve the commotion, news breaks out around the players about conflict in faraway lands, and an NPC approaches one of the players, giving details about how the conflict involves them.

Of course, a Call to Adventure could be thrust upon players, who may find themselves together in a dungeon which acquaints them. This would not exactly be a scene normalcy, but however they find their way out of the dungeon, they will have to choose to not return to their original lives. Regardless, find ways to correlate your players’ backstories to the Call to Adventure and make known why your players would individually be drawn out to adventure. This course of action connects your players deeper than asking them to talk about their characters’ backstories with each other.

Refusal of the Call

This step, if done at all, should be very brief. Its purpose would be to establish ways a character could develop in future sessions. As a Dungeon Master, you may have to do some explaining, such as “You, the Paladin, feel a push from your deity to rid the faraway city of evil, but your flaw, fear of failure, makes you a bit nervous to go.” Do not draw out this step, but give your players something to think about and a way to connect to one another.

Meeting the Mentor

A non-player character, who guides them to their adventure, introduced immediately at the beginning of a campaign is a great way to facilitate roleplay, provide direction to players, and give people a reason to care about the adventure. Campbell suggests that this be the first encounter a hero has after accepting the call. “What such a figure represents is the benign, protecting power of destiny” (‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces,’ pg. 59). Think: Obi-Wan Kenobi and Gandalf.

Crossing the First Threshold

Finish your session with this step to leave a feeling of excitement for the next session. From the Wikipedia article, “This is the point where the hero actually crosses into the field of adventure, leaving the known limits of his world and venturing into an unknown and dangerous realm where the rules and limits are unknown.” Send forth your players into the unknown, finding some reassurance in the mentor and each other.

At this point, the characters find themselves at the “threshold guardian” of their normal lives just before they enter a world of mystery and wonder. “Beyond them is darkness, the unknown and danger. […] The powers that watch at the boundary are dangerous; to deal with them is risky; yet for anyone with competence and courage the danger fades” (‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces,’ pg. 68).

This could look like a dragon flying far above them and toward where their quest lies, a small band of kobolds raiding their party, or entering a mysterious, magic-laden, enchanted forest, hyped up by the town, lore, and character backstories.

Now that you have developed your initial session, the story should begin mobilizing itself with the help of your players. Your next duty as a Dungeon Master is to create conflict in a story-facilitating manner.

Developing Meaningful Conflicts

Conflict drives story. War, internal struggles, good versus evil, natural disasters, devastating powers, and vengeance all propel stories toward their eventual resolutions. However, it is good to remember that a storywriter is writing human stories. Renowned author and lecturer Robert McKee said: “The archetypal story unearths a universally human experience, then wraps itself inside a unique, culture-specific expression.” (‘Story,’ pg. 4). When a Dungeon Master creates meaningful conflict surrounding the human experience, players will naturally advance the adventure themselves. Here are some tips to help a Dungeon Master develop meaningful conflict.

Conflicts Rely on Resolutions

Conflict for conflict’s sake can cause a campaign to lose momentum. Understandably, not every conflict can result in a major shift in the world, but a Dungeon Master would be wise to ask themselves these four questions:

1. “Regardless of outcome, what could this conflict accomplish?”

2. “How does this conflict bring players closer to their ultimate goal?”

3. “How does this conflict help my players develop?”

4. “What results do the possible resolutions of this conflict have on the world external from my players?”

Start your conflicts with less world-breaking consequences and build to an intertwined web of choices. Eragon author Christopher Paolini suggests on his website, “In order to make sense, events are usually arranged in a linear manner that builds from the least to the most important.”

When developing your conflicts, allow for multiple avenues of possible resolution, both peacefully and violently. Author of the Mistborn series and Stormlight Archive, Brandon Sanderson, has developed three very helpful laws for developing a magic system on his blog. Thankfully, because Dungeons and Dragons provides the majority of the mechanics of magic, a Dungeon Master must only decide how common magic is in their campaign and how magic affects the conflicts the Dungeon Master establishes. However, these tips also apply to conflict and resolution. Sanderson suggests:

“If you’re writing a soft magic system, ask yourself ‘How can they solve this without magic?’ or even better, ‘How can using the magic to TRY to solve the problem here really just make things worse.’ (An example of this: The fellowship relies on Gandalf to save them from the Balrog. Result: Gandalf is gone for the rest of that book.)”

Whether players use magical or mundane means to resolve a conflict, consider how this affects the adventure, the characters, and the world, and show those changes in future sessions.

Exciting Conflicts Play on Limitations, Not Strengths

Sanderson’s Second Law beautifully provides guidance on developing meaningful conflicts by explaining that characters are not defined by their strengths, but by their weaknesses. He gives the example of Superman: we could say his “magic” is in his ability to fly and have super strength, but that describes the majority of superheroes. Rather, Superman’s “magic” lies with his moral code of ethics and his vulnerability to Kryptonite.

When developing conflicts in Dungeons and Dragons, you can easily expect players to use their given spells, abilities, and features to overcome challenges. That’s not terribly exciting in and of itself. Superman’s story grips its audience when he overcomes his conflicts in the face of his weaknesses. This will also be the case with your players.

Force your players to find creative solutions to conflicts where their typically-used abilities fail. Make them work hard, make them face their flaws and fears. Give them a challenge that forces them to weigh the possibility of hurting someone by saving others. Have them face their weaknesses, which their enemy has learned to exploit. Fight scenes that are a repetition of spells, abilities, enemy wards, fighting styles, gimmicks, and motivations are uninspiring and leave players unfulfilled.

From Sanderson, “Limitations are more important than abilities. It applies to characters–what they cannot do, what they won’t let themselves do, is more interesting in general than what they can do. It applies to worldbuilding. The costs of living in a harsh world are more interesting, often, than the benefits.“

Work with What You’ve Already Established

Conflict becomes more meaningful when it ties in with what players already care about, what they have faced in part before, or how deeply ingrained it is in the societies and cultures of a campaign. Sanderson’s Third Law “challenges [us] to create deep worldbuilding instead of just wide worldbuilding.”

For example, throwing too many new villains at your party could result in fatigue and confusion. It would be better to develop one or a few villains deeply and have them reoccur in new and challenging ways. Give the villain redeeming qualities, good intentions, nonviolent interactions, a tragic backstory, and plenty of colorful complexity. Even a truly evil-aligned villain should have justifiable motivations. For non-combat encounters and conflict, play on systematic challenges facing cultures, such as economic inequality, oppression, or brutal rites of passage.

Include Riveting Details

Once you get the bug for story creation, you will begin to see world-building inspiration in everything; books, television shows, and historical events are no exclusion. Once you create the “human experience” in your story, you will want to enshroud it in rich, unique cultural specifics.

Develop Cultural Specifics

In context of creating rich, diverse, cultural experiences, Paolini gives great advice on how to add details. This passage was found on his website:

“To help you fill in the details of the world you are creating, imagine that your characters inhabit a real world. Daydream what it would be like to be there. What would your characters eat, what would they talk about, where would they get their supplies, etc. Keep asking the question, ‘What happens next?’”

Prepare these details in advance for players to interact with: climate and environment; which races, beasts, fauna, and flora are native to the land; social, religious, and economic discriminations and hierarchies; phrases and accents unique to the area; strange cultural customs; which trades and services excel or falter; family dynamics; and countless more. Well-storied has a succinct list to help inspire culture creation; Mythcreants has written a thorough article on creating realistic cultures; and Tiana Warner includes a helpful culture-development checklist, for further resources.

Intertwine Non-Player Characters, Events, and Details

Following Sanderson’s Third Law above, creating a web of interconnectedness between non-players, whether they be organizations, societies, deities, or people, can greatly enhance a campaign while limiting the amount of work a Dungeon Master may have.

Intertwine two dichotomously different societies in their origins; have two notable non-player characters join forces or butt heads (this may include employers, villains, or allies); have a non-player character join a cult the party accidentally introduced him to while they were trying to disband it. Separate details, cultures, organizations, and individuals can weave a story when they are brought together.

Give depth to your world by making it seem smaller than it could be. Each life touches another, and each event cascades chains of events until a cataclysm emerges. Let your small details work their way back to the surface to change the world and adventurers.

Conclusion

From the minds of great authors and artists, we’ve experienced just a few tips to enhance our Dungeons and Dragons campaigns: give your players their own Hero’s Journey in a session zero; create meaningful conflict with allowing many resolutions, focusing on player limitations instead of powers, and giving your world depth more than width; and prepare excellent details by telling human stories enshrouded in unique cultural lore.