D&D adventure design guide featured image is credited to Wizards of the Coast and Jonas De Ro. This article contains affiliate links to put gold in our coffers.

Designing D&D adventures can be tough. As Dungeon Masters, we’ve got five thousand ideas buzzing around our heads at any given moment—but actually putting them down on paper, organizing them into something coherent, and whipping them into shape isn’t easy!

That’s doubly true when you’re also responsible for creating tension at the table, building memorable campaigns, and making D&D’s fantasy worlds come alive. Fortunately, screenwriting and novel-writing provide a helpful benchmark for structuring these kinds of stories: the three-act structure.

I’ve written briefly about this approach in the past, but a renewed interest in the Exploration pillar—as well as what the Alexandrian calls “nodes”—recently inspired me to take a closer look at the structure of our adventures—and how we can generalize this approach to side quests, individual adventures, arcs, and even full campaigns.

A Comprehensive Template for Adventure Design

The Three-Act Structure, as it’s classically used, divides a story into three parts: the Setup (Act One), the Confrontation (Act II), and the Resolution (Act III). Significantly, we can—and developers often do—apply these concepts to game design. Why? Because the three-act structure is a refined and proven method for catching and retaining audience (or player) attention, as well as encouraging emotional investment.

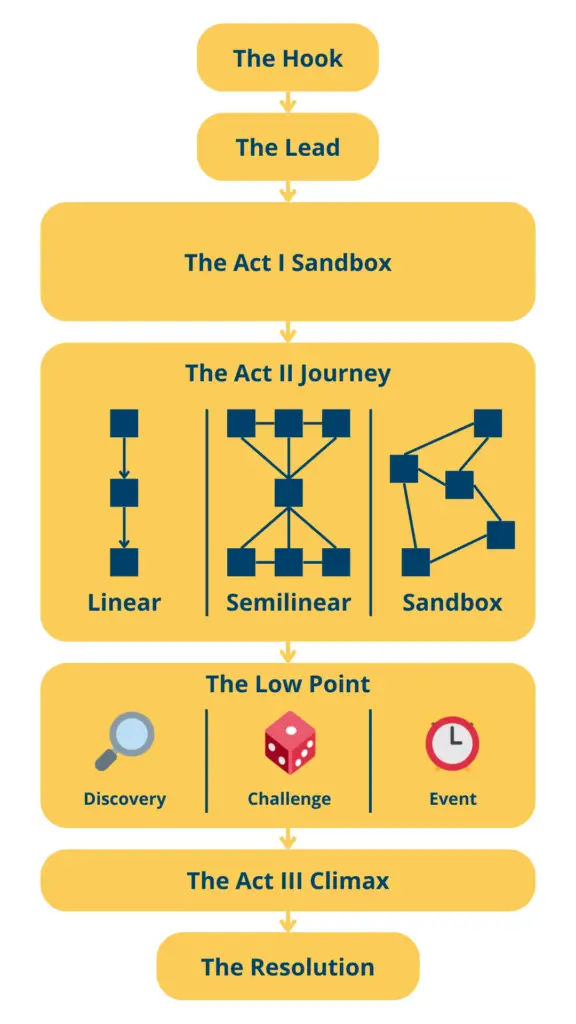

In our approach, we’re going to break these parts down as follows:

- Act One includes the Hook, the Lead, and the (optional) Act I Sandbox.

- Act Two includes the Act II Journey and the Low Point.

- Act Three includes the Act III Climax and the Resolution.

You can see this structure depicted in the graphic below:

Let’s walk through each component of this adventure template to see what they mean and how everything fits together.

The Hook

The Hook serves as the characters’ entry into the adventure. It has three parts:

- A prompt that catches the characters’ attention,

- A connection to the characters’ interests,

- A task for the characters to complete, and

Here, a prompt is anything that’s likely to both (1) interrupt the characters’ current activity or downtime, and (2) draw the players’ interest. For example, this might be a letter that the party receives in the mail.

Next, a connection is any detail that may be connected—even loosely—to a character’s backstory, recent adventures, possessions, interests, or other personal details. For example, the aforementioned letter might be sent from an archmage that the party aided in a recent adventure. Alternatively, the party might be ambushed by members of the Cult of the Dragon, who hope to convince the party’s dragonborn paladin to join them—or die if she refuses.

Finally, a task is any action that the characters must take—or may be encouraged to take—in order to “bite” the hook. For example, the letter might ask the characters to travel to the archmage’s tower for an in-person meeting. Alternatively, opening the letter may itself be the task, especially if the letter contains a magical trap of some kind.

The Lead

The Lead draws the characters—now caught on the Hook—into the world of the adventure. It may be delivered by a non-player character (or by any other means of conveying in-game information) and has two parts:

- Some amount of exposition that explains the forthcoming adventure, and

- A set of clear stakes that will drive the forthcoming adventure.

The exposition expresses or foreshadows one or more themes and one or more threats that the adventure will center on. (Credit to the Dresden Files Role-Playing Game for these concepts.) Here,

- A theme is a certain type of narrative that may appear multiple times in the adventure. For example, the archmage may warn the characters, “Dragons are proud creatures,” or “Beware the Cult of the Dragon.”

- A threat is a creature, group, or phenomenon that threatens the characters’ interests, bonds, or ideals. For example, the archmage may warn the characters that the green dragon Venomfang is expanding her territory, or that the Cult of the Dragon intends to enact a profane ritual.

Each theme and threat should be accompanied by a face—a non-player character that represents one or more facets of that theme or threat. A face has three components:

- A high concept that briefly summarizes the character’s role in the world,

- A motivation that drives the character, and

- One or more relationships to other faces.

For example, the face of the Cult of the Dragon in this adventure may be the half green-dragon warrior Rezmir, with the high concept Cunning Cult-Leader, the motivation “I will win glory and honor for my green dragon parent,” and a familial relationship to Venomfang.

Meanwhile, the stakes give the player characters in-character reasons to go on the adventure, and corresponding goals to achieve. For example, the archmage may warn the characters that the green dragon Venomfang has threatened to raze a player character’s village unless it pays her tribute, or that the Cult of the Dragon has kidnapped the archmage’s child for use as a sacrifice.

By the time the players have completed the Lead, they should have a solid understanding of the adventure’s dramatic question, which will usually take the form of: “Can the characters <complete a goal> before <bad thing happens>?”

The Act I Sandbox

The Act I Sandbox is an optional, but highly useful addition to this adventure framework. Put simply, this is a small, localized collection of non-player characters and locations that the player characters can visit in order to prepare for the adventure to come—either by learning more about the themes and/or threats ahead, or by obtaining useful tools, resources, or allies that could be helpful in the trials ahead.

If you haven’t yet provided the characters with a clear direction or goal, you can do so here. For example, the archmage’s goblin butler may advise the characters that they can most easily reach the cult’s headquarters by chartering a ship at the nearby dock.

You can also use this time as an opportunity to further develop the stakes—for example, by directing the characters to seek out expert information about the Cult of the Dragon from the archmage’s pseudodragon familiar, who is sorrowfully lingering in the child’s bedroom.

The physical area encompassed by this section should be fairly small, and it should be easy for the players to move from one location to another. When the players are ready, they can exit this area and officially begin the adventure.

The Act II Journey

The Act II Journey comprises the “meat” of the adventure—the trials and tribulations that will take the party from the outset of their quest toward the inevitable climax that lies at the end. This might take the form of one or more dungeon crawls, a series of set pieces, or any combination of the two.

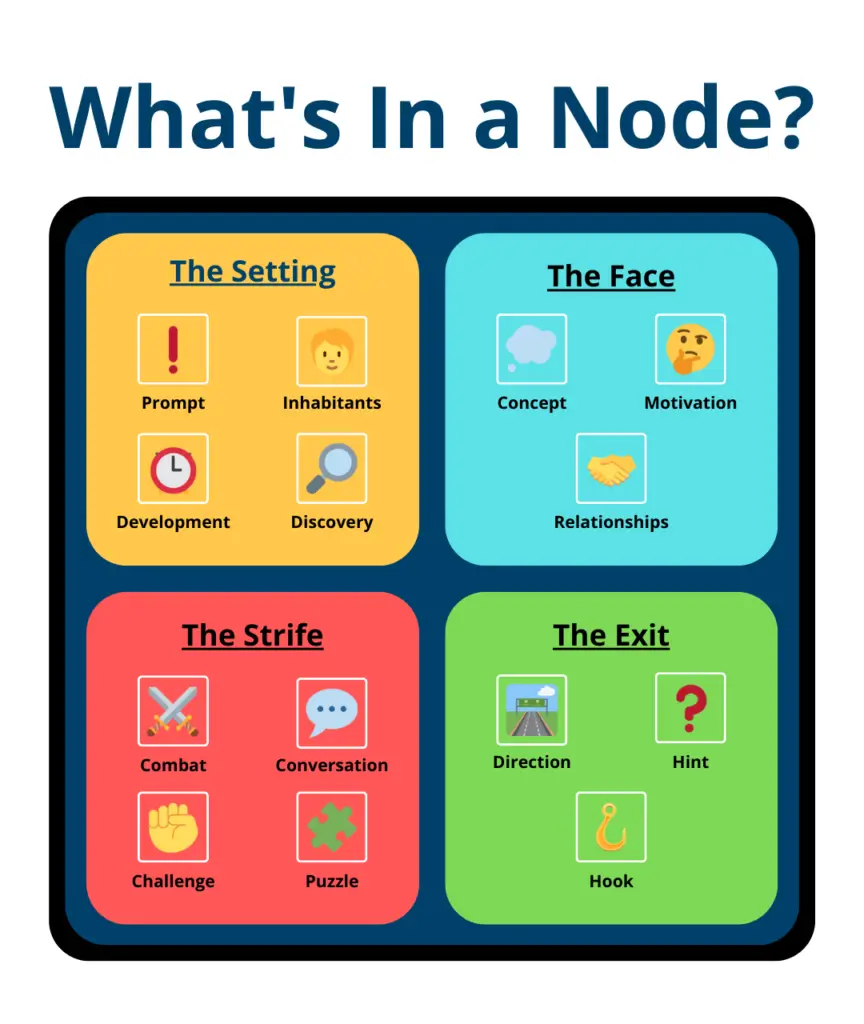

This segment of the adventure is organized into nodes—self-contained locations that each give the players something to do. A single node can be anything—a room in a dungeon, a simple structure, or a notable set piece—and has the following components: a setting, a face, a strife, and an exit.

What’s In a Node?

A node’s setting includes:

- One or more inhabitants can be found there (including both monsters and non-player characters),

- A prompt that catches the characters’ attention,

- One or more developments that occur while the players are present, and

- One or more discoveries that the players can uncover there.

For example, the node The Harbor may host a number of inhabitants, including sailors, merchants, and guards. It might prompt the characters with the visual of a large crowd gathered angrily outside of the Harbormaster’s shack. The characters might discover that no ship is allowed to leave the harbor due to an ongoing investigation—but that one boat, the Sea Breeze, has a reputation for slipping beneath official notice. A subsequent development might reveal that the investigation is led by a disguised member of the Cult of the Dragon—and is targeting the characters themselves!

A node’s face, which is a non-player character that represents some facet of the node, has the same three components as before:

- A high concept that briefly summarizes the character’s role in the node,

- A motivation that drives the character’s actions in the node, and

- One or more relationships to other inhabitants within the node and/or faces at other nodes.

For example, the face of The Harbor might be Gunden Waveseeker, a sailor dwarf who runs a less-than-legal smuggling operation with the high concept “Dockside Smuggler,” the motivation “I’ll do almost anything for a gold piece,” and relationships to the Harbormaster (his enemy) and the night-shift harbor guard (a recipient of his bribes).

A node’s strife constitutes one or more obstacles that the players must overcome to progress the adventure, and might take the form of:

- A combat encounter,

- A conversation with the node’s face,

- A challenge that forces the characters to use certain skills and/or abilities (such as a skill challenge or a stealthy infiltration), and/or

- A puzzle that forces the players to think intelligently and resourcefully (such as an environmental puzzle, a mystery, or a riddle).

For example, The Harbor’s node may include multiple forms of strife: a conversation to persuade Gundren Waveseeker to allow passage on his ship (“It’d take away valuable time from my smugglin’—er, shippin’ contracts”), and a challenge to avoid the cult’s efforts to detain the party upon spotting them.

Finally, a node’s exit provides a path to one or more other nodes, and includes:

- A clear direction toward the next node(s), provided by one or more clues,

- A hint suggesting what the players might find there, provided by one or more clues, and

- A hook (either a push or pull) that encourages the characters to go there.

For example, Gundren may give the characters an obvious clue pointing them toward the next node (“Meet me at the Northern Wharf at midnight, just outside the old warehouse”), a clue hinting at what might be found there (“If you see Sam, the night watchman, just tell ‘im that Gundren’s left a present for ‘im, and he’ll let you pass by”), and a hook encouraging them to get there (“We’ll push off no later than thirty minutes after midnight—if you’re not there by then, we’ll leave without ya”).

Organizing Our Nodes

There are three basic ways to organize nodes in a campaign:

- A linear structure, in which Node A leads to Node B, which leads to Node C,

- A sandbox structure, in which the PCs can visit any of the nodes in any order, and

- A semilinear structure, in which the PCs must visit Nodes A through C in any order before visiting Node D, and

In a linear structure, each node’s exit has exactly one hook, with obvious clues and compelling pushes and/or pulls. For example, the characters might begin at the Northern Wharf, which inevitably leads to the Frozen Strait—a treacherous pass that inevitably leads to the isolated town of Rimespire, where the Cult of the Dragon is hiding.

In a semilinear structure, the adventure routinely switches between a sandbox and linear structure: The characters are unleashed into a small, well-defined “sandbox,” and must visit different nodes in the sandbox in order to assemble the clues they need to visit a preordained “chokepoint node.” Upon completing the chokepoint node, the characters are then released into a new small sandbox. For example, the characters might arrive in the town of Rimespire, where they must investigate a number of nodes—the local Tavern, a Smugglers’ Market, and a Corrupt Temple—in order to find clues pointing toward the Baron’s Manor.

Finally, in a sandbox structure, the players can visit the nodes in any order. Each node’s exit may have an arbitrary number of hooks that lead to one or more other nodes. Here, progression is defined by the players; the adventure will only advance when the players feel that they’ve accomplished and learned enough in this area and are ready to move on to the next one. For example, the Baron’s Manor may lead to the underground Cult Headquarters, containing a nonlinear assembly of cult-related nodes that the characters can try to investigate and disrupt.

Regardless of structure, the characters’ journey between any two nodes might be interrupted by a node that they didn’t expect to encounter. For example, while sailing from the Northern Wharf to the Frozen Strait, the characters’ ship might be stopped by a Pirate Ship node, or might be driven aground at a Deserted Island node by an unexpected storm.

The Act II Journey can use any number of these structures. You might organize the adventure as a single linear chain of nodes, as a semilinear structure that leads into a sandbox, or as any combination of the three types of structures.

Interestingly, the Act II Journey can also be fractal. If you’re planning a long campaign, for example, rather than a single adventure, you can replace each “node” with a self-contained adventure. This works best when you’re planning a campaign with lots of miniature adventures that all build toward a single ultimate climax. (Rime of the Frostmaiden is a good example of a campaign that fits this mold.)

The Low Point

The Low Point is the final beat of the Act II Journey—and the first beat of the Act III Climax. Here, the tension of the adventure comes to a head, forcing the players to confront the specter of failure.

This might take one of three forms:

- A discovery that the adventure’s stakes are far higher than anticipated,

- A challenge—such as a combat encounter—that the characters will struggle to overcome, and/or

- An event that punishes the characters for a failure or miscalculation that they made earlier in the adventure.

For example, the characters might discover that the goal of the cult’s ritual is to summon Tiamat, the Mother of Dragons. They might also be challenged to defeat Rezmir in single combat. They might even face an event in which Rezmir commands them to lay down their weapons and surrender—or else the cult’s hostages will be slain.

In any case, the Low Point poses a final question: Can the characters redeem themselves in the Act III Climax—or will they fall even lower than where they began?

The Act III Climax

The Act III Climax is both simple and complex. It is, most basically, a single node, with all of the things that an ordinary node has—a setting, a face, and a strife. However, the face of the Climax node will be the same face as the adventure’s main theme or threat—and the strife will determine the outcome of the overall adventure.

Here, any development or discovery should raise the stakes of defeat, complicate the characters’ task, provide an unexpected (yet earned) asset, or some combination of the three. For example, the characters may learn that the cult has already begun the ritual, and that the growing portal allows Tiamat to defend her followers from afar. Alternatively, the characters may find that a cult member they showed mercy to earlier in the adventure has decided to join them against the cult.

Meanwhile, the strife of this node should require resourcefulness, thoughtfulness, and tact. The players must draw on the resources they’ve gained over the course of the adventure—from allies to knowledge and magic items—and use a cooperative strategy to overcome a truly formidable challenge.

The Resolution

The Resolution is exactly what it suggests—an opportunity for the characters to tie up loose ends and enjoy the satisfaction of completing the adventure. There are no particular hooks or nodes to develop here—instead, just get a sense of what your players would like to do, and prepare accordingly.

When this segment of the adventure has come to an end, you can either introduce the Hook of a new adventure, or allow the players to enjoy a period of downtime first.

Conclusion

It’s important to remember that, unlike a movie or video game, an adventure in Dungeons & Dragons is truly “open-world.” While we can try our best to funnel our players by offering well-baited hooks and clear sets of directions, even our best-laid plans may go awry. At the same time, few DMs have unlimited time to prepare campaigns. In many cases, DMs might prefer to create the adventure on-the-fly, rather than planning everything out upfront.

Still, this adventure structure isn’t a straightjacket, but a signpost—it’s something that we can look to in order to get an approximate idea of where we are, where we’re going, and how we might get there. You don’t need to use this template to plan everything out from the beginning—but you can use it as a reference point whenever you’re pondering how to structure your upcoming side quest, or how to fit the pieces together when you’re finally ready to wrap things up.