Featured image for D&D combat tactics is credited to WotC.

Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links that add gold to our coffers.

You’ve decked out your Half-Elf Wizard with the best gear, the best spells, and—you hope—the best one-liners. But now you’re standing in the middle of combat, frantically sorting through your character sheet and wondering: What do I do next?

“Strategy without tactics,” writes Sun Tzu, “is the slowest route to victory.” With a strong grasp of D&D 5e’s fundamental combat tactics, however, any player—or DM—can pave a clear path to triumph. These eight, class-neutral, tactical tools will make your (N)PCs smarter, hardier, and—most importantly—more efficient:

1. Abuse Cover Relentlessly

2. Funnel Your Foes

3. Learn to Love (Getting Hit by) Opportunity Attacks

4. Focus Your Fire

5. Help Stronger Combatants

6. Attack from Darkness (or Fog)

7. Drag Enemies to Damage

8. Coordinate with Allies

1. Abuse Cover Relentlessly

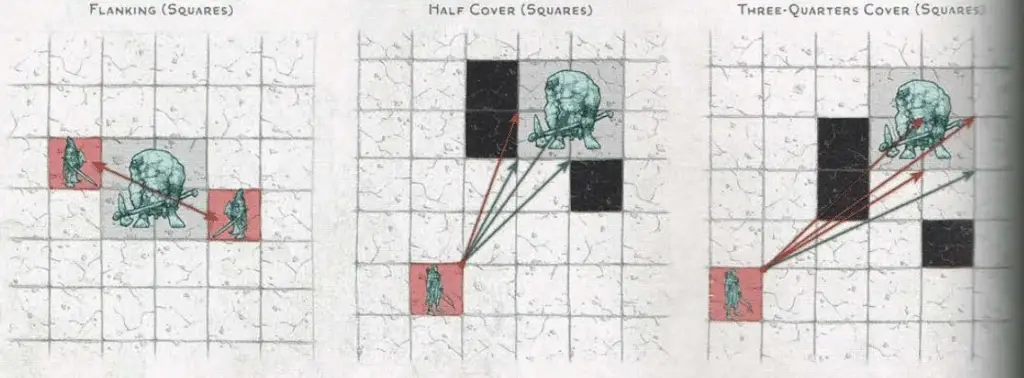

Shields are a mainstay of 5e martial classes, but cover can provide even the squishiest of sorcerers with equivalent—or greater—protection. From walls to debris and even other creatures, cover is everywhere—and its benefits, given 5e’s bounded accuracy system, are immense.

An ogre’s javelin (+6 to hit) has a 70% chance to hit a 3rd-level sorcerer with AC 13—and with 2d6 + 4 (average 11) damage, that’s no joke for a character with 20 hit points. If that sorcerer is behind half-cover (+2 to AC), though, that’s only a 60% chance to hit; with three-quarters’ cover (+5 to AC), the poor ogre has only a 45% chance to hit, reducing its expected damage from 7.7 points to 5. WIth full cover, of course, that expected damage drops to zero.

If cover is available, get behind it! If you can end your turn behind full cover—i.e., in a place where neither you nor the enemy can see one another—so much the better. (After all, no one is stopping you from running fifteen feet forward, firing a crossbow bolt, and then running fifteen feet back into hiding).

If you can’t find cover, make some! Overturn a table, conjure an illusion, or place a hardier ally between yourself and your foe (crafting a cozy +2 half-cover bonus; the paladin will surely understand). If cover is completely absent, drop prone to impose disadvantage on ranged attackers, which can offer as much as an effective +5 to AC! (Just remember to stand up on your next turn before attacking, and to keep at least thirty feet—or the enemy’s approximate move speed—between you and the nearest foe).

2. Funnel Your Foes

By funnelling enemies through a choke point, savvy adventurers can create an artificial advantage in the action economy, forcing single foes to defend against attacks from multiple angles. If that choke point is defended by tanky, defensive characters while low-health mages hurl firebolts from afar, so much the better!

Not only can the defending party focus its attacks on a single foe at a time (see “Focus Your Fire” below for more information), it’s also well-defended from ranged and melee attackers who can’t fit through the choke (see “Abuse Cover Relentlessly” above). By filling the choke point with tactical equipment such as oil, caltrops, or ball bearings, the defending party can further hone its advantages.

3. Learn to Love (Getting Hit by) Opportunity Attacks

PCs and monsters fight equally well whether they’re at full health or a single hit point. Though it’s true that 5e is a game of attrition, it’s also true that the only hit point that matters is your last. Hit points, like all resources, are simply a means to an end—and opportunity attacks are a perfect chance to spend this currency.

Opportunity attacks deal damage, yes, but players (and DMs) often overvalue the danger of this “extra” attack. Consider an archer retreating from a cyclops. On its turn, the cyclops can use its Multiattack action to make two attacks with its greatclub, dealing an average 38 (ouch!) bludgeoning damage. An archer who Disengages before retreating thirty feet still leaves a window for the cyclops to close the distance and attack twice again.

An archer who Dashes away, however, can retreat a full sixty feet, forcing the cyclops to do the same if it wishes to give chase. With its action spent, the hungry cyclops can, at best, hope only for a single opportunity attack should the archer retreat again, cutting its damage output in half.

Not all monsters (or PCs) have Multiattacks, but many have strong, Action-only attacks. Consider the vrock’s Spores or the stone golem’s Slow. By Dashing away, a character can force their foe to decide between choosing easier prey or giving an indefinite chase. The retreating party, of course, is better off either way—after all, it’s better to beat a path back to higher ground, well-known terrain, or the other side of a choke point than to flounder on a hostile battlefield.

4. Focus Your Fire

In D&D 5e, the “action economy” is king: The side that takes more actions per turn usually wins. The inverse is also true: The side that takes fewer actions per turn usually loses. To reduce the number of actions that your opponents can make, reduce the number of opponents.

Picture a fight between three 3rd-level Human Fighters and three bugbears. On their turns, the fighters (wielding greatswords) each attack for 2d6 + 3 (average 10) damage. On their turns, each of the bugbears attacks for 2d8 + 2 (average 11) damage. Each bugbear has 27 hit points. If each fighter attacks (and hits) a separate bugbear, all three bugbears (still standing with 17 average hit points) can then, on their own turns, strike back for an average sum of 33 damage!

But if the fighters gang up on (and hit) a single bugbear, they’ll deal an average total of 30 damage—immediately knocking that 27-hit point bugbear out of the fight! On the bugbears’ turn, only two bugbears are still able to attack, reducing their average damage from 33 to 22. By doing nothing more than changing the target of their attacks, the fighters have reduced the bugbears’ damage output by 33%—and increased their own likelihood of victory by far more.

Who should you prioritize? Keep an eye out for the enemies who are (1) closest to death (to maximize your early KOs), and/or (2) most dangerous to you and your allies (to stop the enemy from using this tactic first).

(A cautionary note to DMs: An unconscious PC is an unhappy PC. Think very carefully before using this tactic on your players and unleashing a death spiral on your unsuspecting party.)

5. Help Stronger Combatants

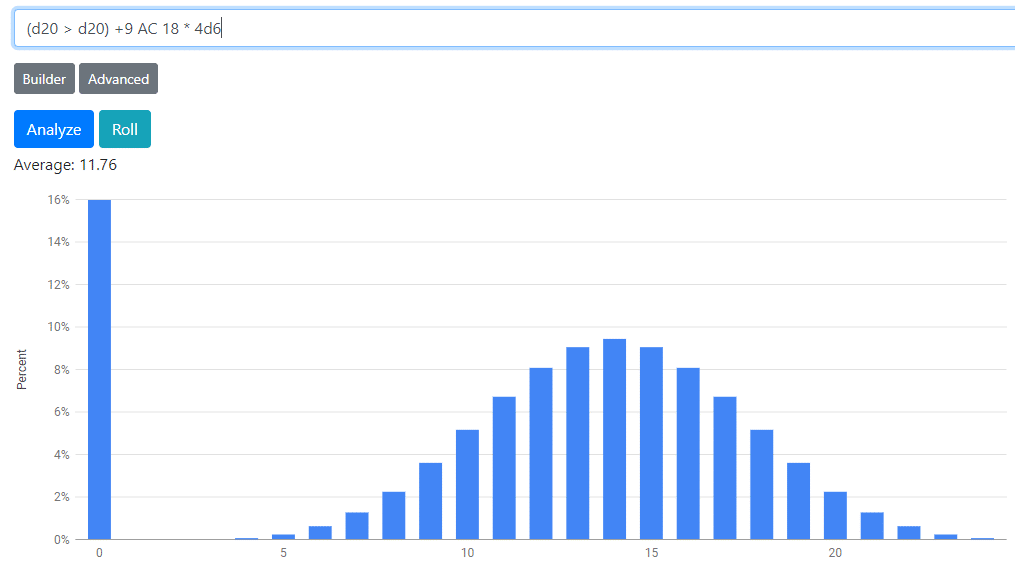

When you’re a small fish in a big combat, it can be tough to feel like you’re making a contribution. A fearsome vampire lord, with a +9 to hit, may deal a stunning 4d6 necrotic damage on a hit—but the swarm of bats accompanying him, with its +4 to hit and 2d4 piercing damage, may struggle to hit a party of high-level PCs. What’s a small fry to do? If the minion is sufficiently low-power, it may be better to forgo attacking and take the Help action instead!

Using a handy-dandy dice probability tool, we can see that, against a PC with an AC of 18, a swarm of bats at full health will deal an expected 1.75 damage per turn. Without advantage, our vampire will deal an expected 8.4 damage against that same PC. If both attack separately, the PC will suffer an expected 10.15 damage.

What if the bats take the Help action instead, granting the vampire advantage on his first attack? Our vampire’s probability of hitting goes up—and so does his expected damage, increasing from 8.4 to 11.76 damage. It’s not an enormous increase, but when efficiency is the goal, every point of damage—and every source of pressure—counts. The greater the damage disparity between the monster and its minion (and the greater the target’s AC), the bigger the payoff for Helping instead of attacking.

6. Attack from Darkness (or Fog)

Picture a lizardfolk and a grung on opposite sides of a darkened room. If either attacks the other, advantage (from attacking a “blinded” target) and disadvantage (from attacking while “blinded”) cancel out. But if only the lizardfolk is standing in darkness, however, only the grung (which can’t see the lizardfolk) is blinded, granting its attacks disadvantage and granting the lizardfolk advantage. If both parties are holding torches, it’s clearly to the lizardfolk’s benefit to extinguish its own torch first, summoning a shield of darkness.

Creatures struggling with disadvantage (e.g., a vampire exposed to sunlight) or defending against advantage-fueled attacks (e.g., a party without darkvision fighting drow in the Underdark) may also benefit from new environmental conditions that cancel those penalties (or benefits) out. Fog cloud may not do much on its own—but it does inflict simultaneous advantage and disadvantage (which cancel out) within its radius. Because advantage and disadvantage can’t stack, then, a vampire caught in a sunbeam would do well to summon a fog bank to empower its attacks.

7. Drag Enemies to Damage

A Grapple replaces an ordinary action (or attack, for characters with Extra Attack), which gives grappling a high opportunity cost. A successful grapple won’t defeat an enemy—but a successful attack certainly can. As such, grapples should be used only where they will do the most good.

A grapple followed by a Shove action is a great boon on a success (bestowing advantage to the target’s attackers and imposing disadvantage on the target’s attacks), but unreliable—even if the grappler has a 75% chance (i.e., the grappler has a +6 advantage over the target—e.g., +7 Athletics versus +1 Acrobatics) to win either contest, that leaves only a 56% probability (75% x 75%) of winning two contests in a row (a grapple followed immediately by a shove). (It’s worth noting that a +4 advantage—e.g., +6 Athletics versus +2 Acrobatics—is the smallest worthwhile advantage, granting a respectable two-thirds chance of success).

If the combat has several rounds left—and the grappler has an Extra Attack or a big advantage (e.g., +9 Athletics versus +1 Acrobatics or more)—the long-term disadvantage imposed on a pinned target is worth the gamble. Otherwise, though, grappling works far better when the grapple increases the party’s overall damage output. Consider the following:

- A raging barbarian dives off of a cliff, knowing that they will survive the fall—but the grappled mage alongside them surely won’t. (Can you say, “suplex”?)

- A fighter drags an enemy hobgoblin through a choke point, removing it from cover and allowing their allies to easily (and safely) focus their fire.

- A paladin hauls a hostile bugbear toward its goblin allies, expanding the effective radius of the sorcerer’s fireball.

A 5th-level paladin’s multiattack might deal 9 expected damage against a 27-hit point bugbear—but a 5th-level sorcerer’s fireball will deal an expected 12 (assuming a 75% chance of a successful grapple), if only the paladin can drag it into range. (Don’t forget that a successful grapple will continue to pay off each round that it lasts).

Grappling can also be useful defensively, especially against skirmishers and mobile brutes. For example, a successful Grapple can shut down a dagger-and-disengage Halfling Rogue, or hold back a hulking ogre from attacking squishier targets. Because it’s so enemy-dependent, though, don’t expect it to come up that often.

8. Coordinate with Allies

From focused fire to grapples, several of these tactical tips rely on teamwork—the strongest force in D&D. The action economy might favor the side with the greater number of actions, but if all else is equal, the side with greater coordination will nearly always come out on top.

Characters with abilities that manipulate the battlefield or debuff enemy combatants—such as bards, wizards, or druids—can often make the best use of these strategies. Does your sorcerer know polymorph? Cast mind sliver to decrease the target’s Wisdom saving throw. Does your cleric know spirit guardians? Grapple a powerful foe and drag them into the meat grinder. Is your celestial warlock about to hit a vampire with a 4th-level guiding bolt? This sounds like a job for bardic inspiration (and perhaps a Help action).

The strongest teams synergize their abilities, choosing spells and abilities that resonate with their allies’. To bring those synergies to their full potential, however, communication is key. About to drop a lightning bolt? Ask your barbarian to drag the villain’s lieutenant into the line of fire. Looking for the finishing blow on a towering brute? Invite your cleric to follow up your hold person with an auto-critical, upcast inflict wounds. The possibilities are endless.

Conclusions

Like many games, D&D 5e is a strategic and tactical experience—but character-building guides can only take you so far. With these basic tactical options in mind, however, even the most unoptimized PC (or the weakest NPC) can play a powerful role in combat.

In isolation, a character sheet and a D&D party are just disparate, lonely pieces. Taken together, however, the integrated whole is far greater than the sum of its parts.

About the Author: DragnaCarta is a guest writer for FlutesLoot.com and a veteran DM with 12+ years of experience. He is the author of the popular “Curse of Strahd: Reloaded” campaign guide and the Dungeon Master and director for the Curse of Strahd livestream “Twice Bitten.” You can get his personal RPG mentoring plus early access to projects by joining his Patreon.

Cast Message in the comments section below to ask DragnaCarta about Van Richten’s Guide to Ravenloft. You can find other articles by DragnaCarta on FlutesLoot.com:

Combat tactics are fun to play around with as a party. Several times I’ve felt a little bored as a ranger or warlock standing in the back and saying, “So anyway I start blasting”. And while that is usually the best move in the heat of combat, it can be way more fun to get creative with utility options. As great as a crit on an eldritch blast feels…using spells or other mechanics to isolate a foe can be even more satisfying. Banishing a big baddie and mopping up their goons before bringing him back. Summoning things you can’t control in the middle of the bad guys to watch the chaos unfold. Blasting or telekinesis enemies off of cliffs. It’s great stuff. And if all else fails…of course I can start blasting again!

Hi Ian,

I completely agree with you. Playing this game for many years makes me want to actively search for interesting (sometimes better) actions to take in combat. There’s much fun to be had by putting thought into alternative tactics to go beyond default, predictable choices.

I think the value of dodging is not properly noted in this piece. It’s fundamental to tanking and battlefield control and any form of choke-point fighting. In fact, it’s so powerful in terms of reducing damage/eliminating crits that finding the bottleneck to make use of dodge should be a first step in the vast majority of combats.

A brief mathematical example… Let’s say your tank (AC 20) is holding a corridor against a single troll. For purposes of the example, let’s assume the troll can’t get by the tank, but also does not have disadvantage on his attacks due to being squeezed. The troll has 3 attacks which each require a 13 to hit prior to adjustment (40% chance). With disadvantage imposed by dodge, the chance to hit each attack drops to 16%, which is a 60% reduction in damage inflicted prior to consideration of critical hits.

Prior to critical hits, the troll was expected to do 40% * [1d6 +4 + 2d6 + 4 + 2d6 + 4] = 40% * (5d6 +12) = 40% (29.5) = 11.8 damage

With the tank dodging, that drops to 4.7 = 16% * (29.5)

Adding consideration for critical hits, the difference becomes bigger.

The chance of a critical hit drops from 1 in 20 to 1 in 400 (both rolls must be natural 20), which results in a further significant reduction in damage.

Troll attacking against a non-dodging opponent hits normally 35% of the time and crits 5%, making expected damage:

35% * [1d6 +4 + 2d6 + 4 + 2d6 + 4] + 5% * [2d6 +4 + 4d6 + 4 + 4d6 + 4]= 10.325 + 2.35 = 12.7 rounded

That same troll attacking that dodging opponent hits 15.75% of the time and crits 0.25%, making expected damage:

15.75% * [1d6 +4 + 2d6 + 4 + 2d6 + 4] + 0.25% * [2d6 +4 + 4d6 + 4 + 4d6 + 4]= 4.646 + 0.1175 = 4.8 rounded

So after consideration for critical hits damage is reduced by 62.2% and the absolute difference in expected damage changed from a reduction of 7.1 per round to a reduction of 7.9 per round.

How does that impact combat overall? Let’s say your tank is 4th level and has 40 HP. normally he would be killed by the troll in 4 rounds, but by sacrificing his own attacks, he becomes an odds-on favorite to survive 8 rounds toe-to-toe with a troll (prior to any healing) while his companions finish the creature.

That’s a fantastic point, and one I wish I’d included! Mathematically speaking, you’re right that the best thing for a tank to do is often just take the dodge action (especially if they have the Sentinel feat). Unfortunately, I don’t see many players willing to do that, but I’m willing to be wrong about it.

I hear your point about tanks not wanting to be regular dodgers from other GMs, but in both games I play (1 as the tank, another as a wizard who supports bottlenecks), it’s the primary combat tactic when the battlefield environment allows.

I think part of what makes dodge fun is the ability to weave it in with Battle Master abilities like riposte, bait and switch, and brace.

I love this kind of playstyle. Defense and support are roles I’m more than comfortable with. Using the Dodge action is more than a viable choice, which you made clear!