Featured image from the Dragons of Icespire Peak adventure.

This article contains affiliate links that add gold to our coffers at no expense to you! Support our small business by using our links. Thank you!

✤ ✤ ✤ ✤ ✤

I’ll admit, I’ve written somewhat about this topic before, but only because it weighs heavily on my mind when I run a game. As a player who doesn’t particularly enjoy combat, I’ve narrowed down what issues I have with combat and a simple formula to spice up fights in gameplay. These steps take little effort to incorporate and have been tested in my own games.

What Makes Combat Unenjoyable

To understand where I’m coming from, I’ll explain myself briefly. I’m not a min-maxer. I enjoy playing characters with lots of utility. I love a good story, and I enjoy roleplaying meaningful moments.

Periodically, combat seems to disrupt the story. Combat simply for combat’s sake seems rote and unnecessary to me. We have to win this encounter to move on, and it uses up valuable resources, especially for spellcasters. When it’s a straightforward encounter of hit, to hit, to hit, the game becomes monotonous and my heart doesn’t go into it.

Furthermore, I like a good puzzle, but not a “solve this pattern or fall into lava!” in-game puzzle. I like combat that feels more like chess where I can set myself or my teammates up strategically to achieve some great synchronicity and skill. Combat is often constructed as a basic battlefield with monsters spawned, and that’s the thick of it. Not only is that set up not engaging, it’s infuriating. This sentiment leads perfectly into its solution.

3 Steps to Improve Combat Encounters

Start with your basic encounter. Draw out your space, place your opponents on the map. Then follow these steps:

Step 1: Incorporate interactive terrain elements.

Whether beneficial to utilize or detrimental to players, interactive terrain elements add an additional dimension to any battlefield. These terrain elements give the players a sense of freedom and problem-solving in addition to fighting creatures. Whether the terrain gives players cover, advantageous positioning, extra utility, or difficulty to navigate, your players are sure to find the encounter far more intriguing based on this incorporation.

I’ve listed out about 18 “Interactive Battle Map Elements” in this article to inspire Dungeon Masters with ideas to include. Check it out, and see below how I would integrate them into basic battles.

Step 2: Give your monsters unexpected abilities or tactics.

Experienced players know what to expect when they fight a goblin, lich, or a gelatinous cube. Those monsters, and many others, are used often enough that players think they have a handle on the situation. However, you can subvert these expectations when you give your monster additional yet reasonable attacks and strategies.

Peruse this list of legendary and lair actions, then think about adding either a “boss” to your encounter with a few of these actions, or think of a unique ability you can give to each of the creatures in your encounter.

Focusing on tactics, monsters can work together or utilize the environment to attack uniquely and unexpectedly. Think about how the monster would utilize the land, such as an Aurumvorax (gold-eating multi-legged large ferret, more or less) tunneling from above to cause falling rocks players must dive away from (Dex ST DC 15, 2d6 bludgeoning damage). Or a Green Hag dragging a player down into her murky bog to attempt to drown (Strength ST DC 14, grappled and dragged underwater).

Continue onward to see how I would incorporate this step into battle prepping.

Step 3: Add something meaningful to the players or story.

Not every encounter has to push the narrative perfectly. Some encounters will add details to further player goals, some will make the characters choose morally or immorally. Adding some sort of narrative element to the encounter will keep players immersed and involved, as the encounter now has meaning beyond garnering experience points and possible loot.

Players may choose to capture and interrogate a minion, they may overhear talk of future plans from the shadows of a villain camp, or perhaps a player recognizes an article of clothing belonging to their long-lost sister used by an opponent.

See how I might include narrative details in the next section!

See These 3 Steps in Action

To fully present these ideas altogether, I’ll create three battle scenarios below, then add in my elements and run through how that would possibly look in-game. This simulation will hopefully show just how much more rich an encounter can become.

I’m using Inkarnate to create the following maps, but any method, such as drawing on a whiteboard or using tokens or figs, can show the diversity of a map for players to see. Also, feel free to download and use the maps below for your own games!

Scenario 1

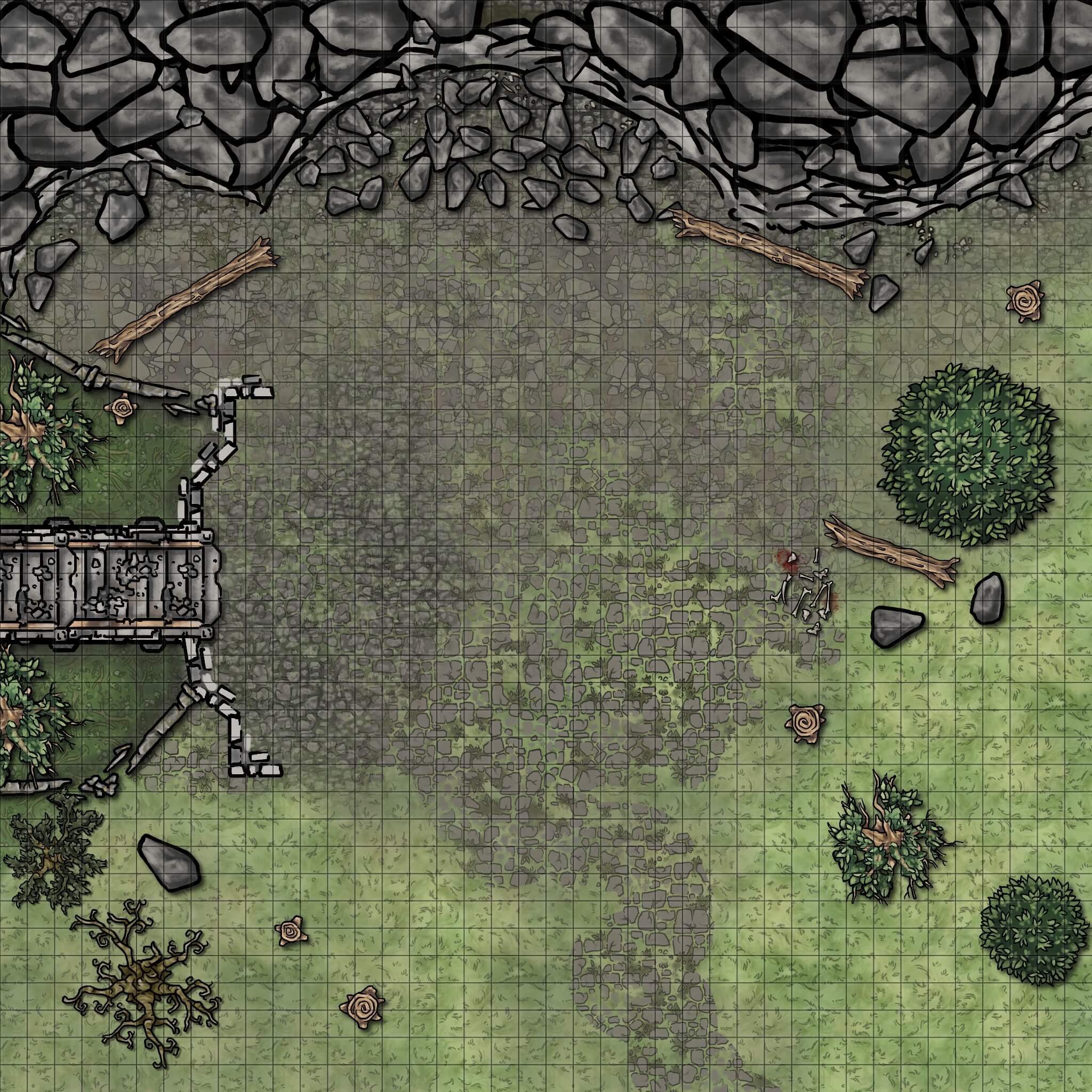

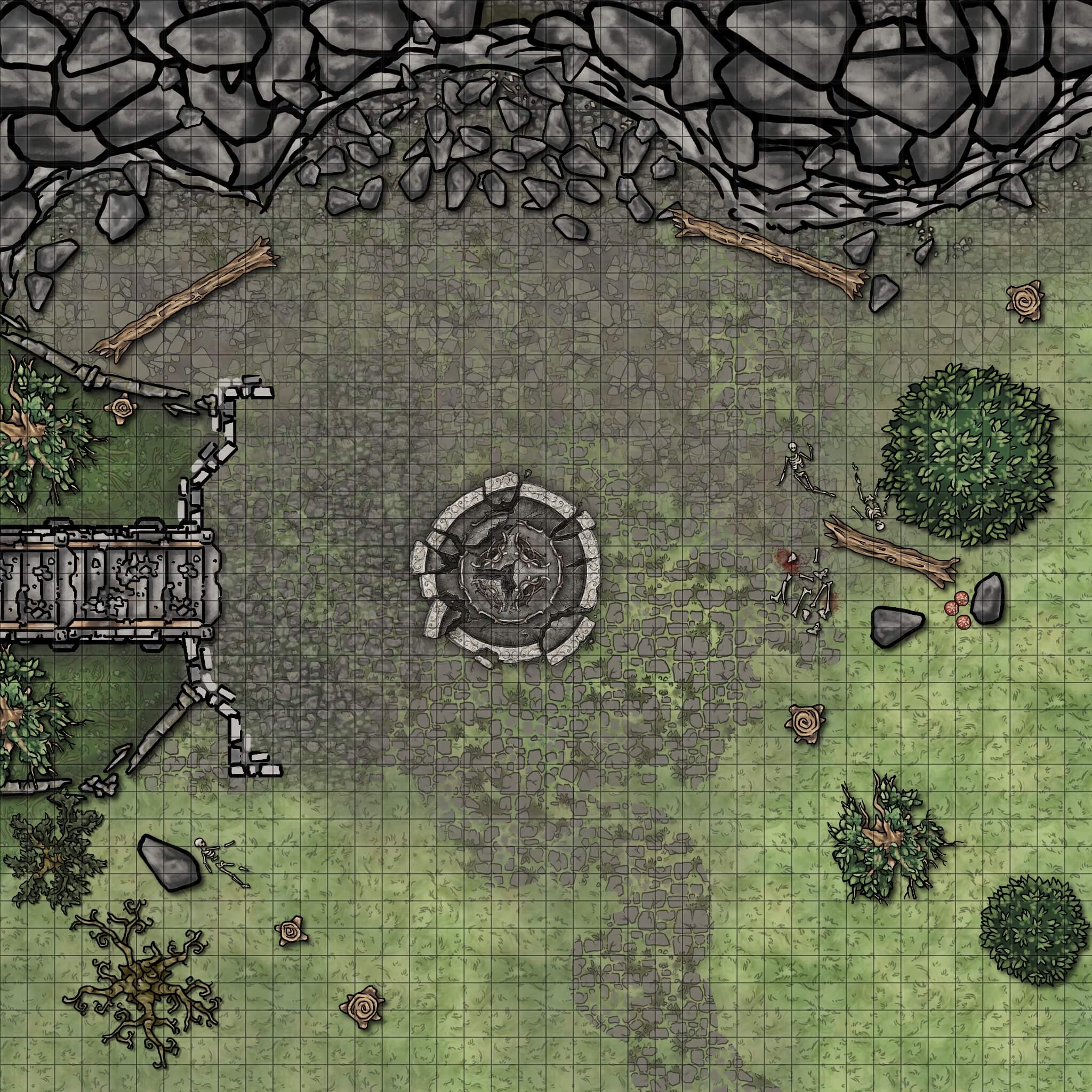

The traveling party comes across a small camp of eight goblins within a forest clearing (CR 2 encounter).

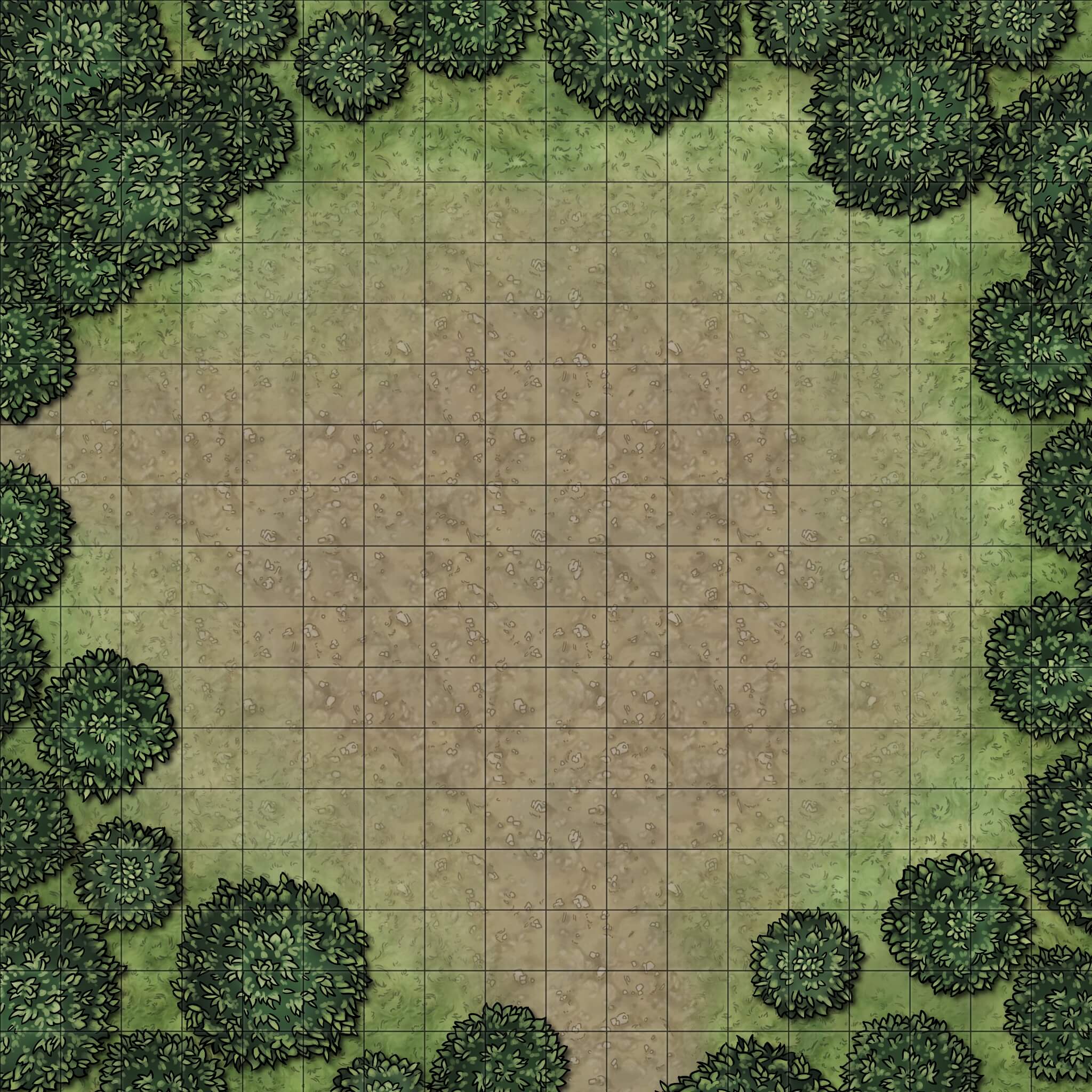

Simple Battlefield:

This is simply a forest clearing. Trees surround an area of dirt and grass. Goblins just happen to be there. Players will either have to sneak past the camp, defeat all eight goblins, or find a way to get them to run off or peacefully allow them to pass.

There’s not much to this encounter except how players choose to handle the situation. Personally, I’d try to pass by undetected simply to avoid combat.

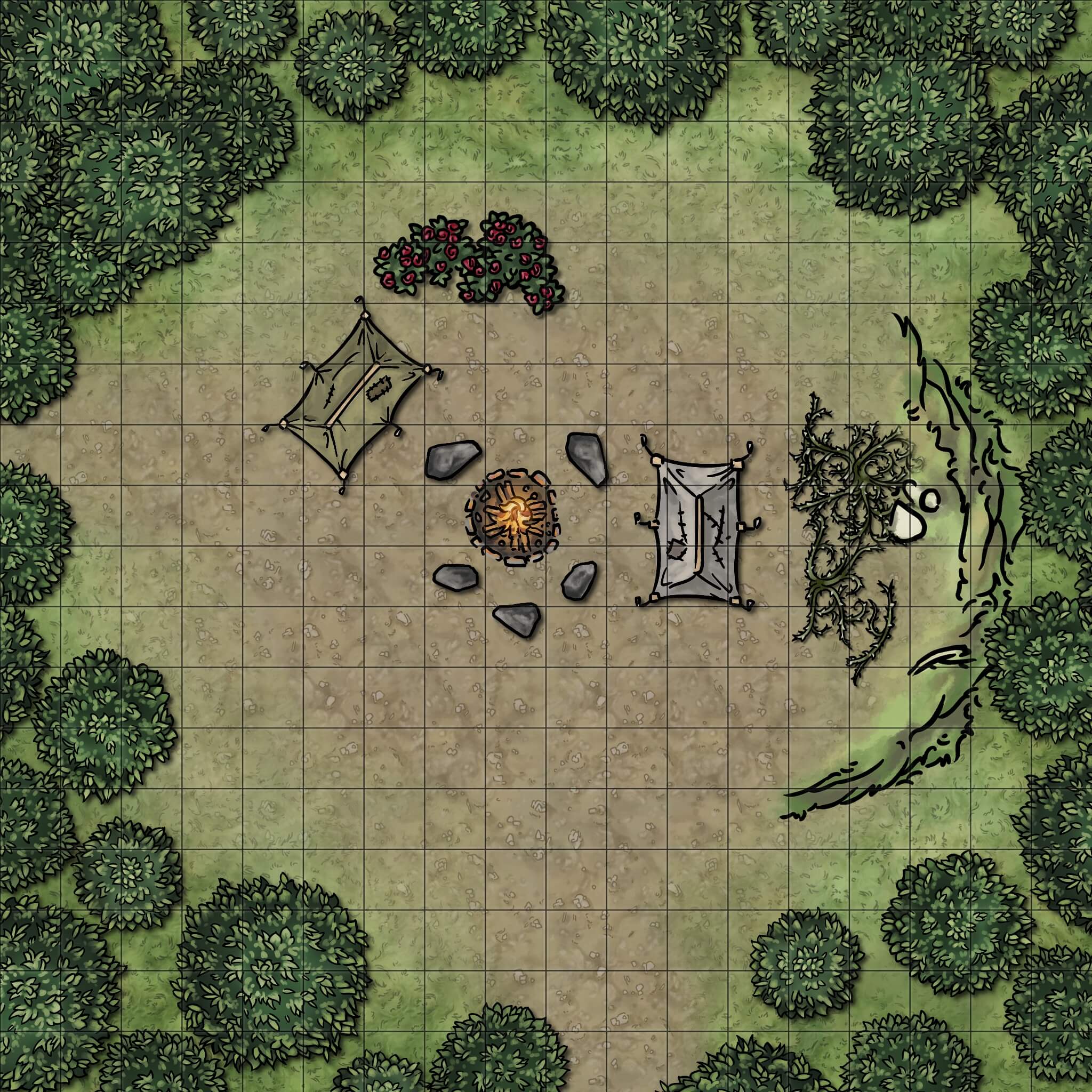

Step 1 – Interactive Environment:

Add in a few interactive elements, like an actual campsite with a ring of fire, some boulder seats, a few thorny rose bushes, and some tents. Plus, let’s raise the camp on a hill which dips off on the right-hand side.

Now, players can more easily devise a plan of attack or avoidance. Will one player create a diversion at range from the protected hillside while the rest of the party sneak attacks from the treeline or behind the tents and roses?

Perhaps there are more goblins in the tent that players are unaware of. This can add an element of surprise or suspense on the goblin’s end of things.

Step 2 – Unexpected Abilities and Tactics:

Using the same map, consider making one goblin the camp leader. She’s a bit smarter than the rest of the goblins and has devised some mechanical traps on the outskirts of camp so that they don’t get caught unaware. These can be crude trip lines that ring a tin can alarm, or perhaps a hidden pike pit has been set up (to catch prey to eat or enemies skulking about). Check out this list of mechanical traps that a smarter goblin leader could easily set up.

Goblins are also known to keep small creatures as pets, so perhaps adding in a honey badger or a swarm of rats to the battle will add unexpected excitement! Keep in mind your encounter’s challenge rating when planning these tactics.

Additionally, goblins may get pack tactics (advantage on attacks when an ally is adjacent to the target). The goblin leader may utilize her legendary action economy of activating a magical ring that allows her to use one cantrip per round; taking extra movement without provoking an opportunity attack; or kicking up dirt to blind a target until the end of the goblin leader’s next turn (Constitution ST DC 11). Again, keep CR at your forethought before adding in too many difficult twists.

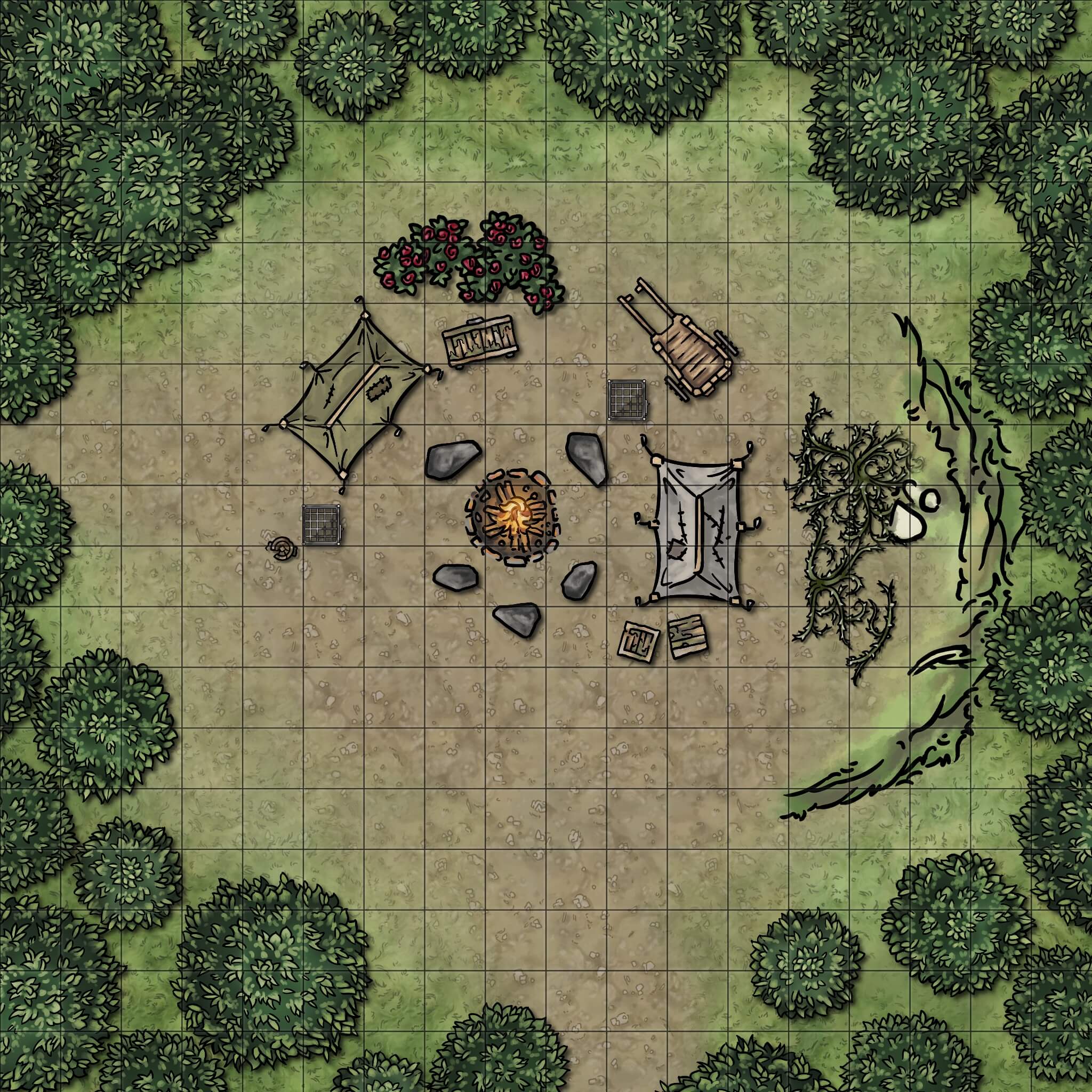

Step 3 – Add Something Meaningful to Players:

This final version of the map shows additional elements: musty crates, a broken urn, two cages, and a small handcart. Besides the chance to score some loot, players may find something they’re looking for in the crates or cages. Maybe the crates hold a kidnapped familiar or small humanoid. The question then arises: what are the goblins doing with a hostage? Are they working for someone else? This basic encounter may spark a larger quest at the beginning of a campaign.

Additionally, personal effects of the goblins may be found in the tents or crates that tie into player backstories. A handwritten note from a well-known nobleman may inspire a paladin to investigate as part of their charge to root out corruption. A mildew-stained book may be discovered within the crates, among other seemingly trash items, which an academic player may decipher to learn of the history of the region. A carved druidic wooden necklace may indicate this band of goblins is responsible for the decimation of a firbolg village nearby, kin to a player character.

The possibilities are endless when you slide in one or two personal details that relate to the campaign, quest, or backstory of characters.

Scenario 2

Players have been asked to defeat a hill giant that has been terrorizing local and defenseless villages, eating livestock and unfortunate villagers. After searching nearby hills, players find him napping on the hillside, belly full with spoils of his raid (CR 7 encounter).

Simple Battlefield:

This battlefield is an open hillside. The giant could be lounging under a tree or against a rock, but for the purpose of this exercise, I’m going to assume nothing is on the battlemap just yet. Believe it or not, I’ve had fights like this: absolutely blank canvas except the creatures we’re fighting. Talk about uninspiring!

Additionally, with this battlefield, we’re limited to a very uncreative hill giant. He can use his club, and I suppose a Dungeon Master can claim the giant digs up a rock from underground to toss, but that’s basically the extent of his abilities here. Let’s spruce up the map and see what we can come up with.

Step 1 – Interactive Environment

Let’s suppose the hill giant has made his home at the ruins of an old castle, destroyed in some ancient battle hundreds of years ago. The giant has been cozying up to the rocky wall, smashing apart the remains to his liking. It’s a good central location: far enough away from the major villages for a mob to run him off, yet perfectly nestled within a day’s distance of farms and livestock grazing grounds. This hill giant has found his paradise.

The hill giant has plenty of rocks to throw, and nobody can really sneak up from behind, given that massive pile of rocks. Broken cobblestone may be difficult terrain for players (but possibly not for the hill giant, who has a larger surface area).

However, the hill giant may be too large and heavy to cross that derelict bridge without risking its collapse. This may be a good bottleneck space for players to act out ranged attacks. Players may also use the trees as cover, hoping the hill giant doesn’t just uproot them. They could even try to scramble up the top of the ruins and cause a rockslide to bury the giant.

Step 2 – Unexpected Abilities and Tactics:

Besides throwing rocks, the hill giant may grab or uproot tree trunks to sweep players off their feet (area of effect attack, 10 ft cone in front of the hill giant, dexterity ST DC 17, thrown 10 ft., 3d10 bludgeoning damage).

I might even consider allowing the hill giant to climb atop the rubble of rocks and jump to the ground, creating a small-scale Earthquake effect (see the Earthquake spell, but limit its range to Self and radius to maybe 50 feet). A dimwitted hill giant may not think about the consequences of creating an earthquake, such as destroying the bridge or causing an avalanche of rocks to his detriment.

Giants may also subjugate or allow the company of weaker giants, large carrion, goblinoids, and so forth. Maybe an owlbear clan also made a home in the castle ruins, and awaken angrily from a rockslide or earthquake. The owlbears may fight against the hill giant and the players indiscriminately.

Step 3 – Add Something Meaningful to Players:

A large broken fountain with elven runes adorns the entry path to the destroyed castle. Humanoid bones litter the lair, clearly devoured by the giant. A small patch of red mushrooms grows by the slumbering giant.

Players may feel more inclined to engage the giant, knowing it is eating humanoids. A player could recognize a locket or special weapon from an NPC they had met earlier in the campaign and try to ascertain the fate of their friend.

A druid or herbalist character might recognize the mushrooms as prized and rare due to the strict growing environment, which requires bloodmeal to grow. Given these mushrooms are growing among the pile of discarded corpses, this may present an intriguing opportunity for characters to find a secret ingredient they’ve been interested in.

The castle ruins may be tied to the ancestry of an elf player. As we learn from chapter 2 of Mordenkainen’s Tome of Foes, elves are reincarnated, unable to return to their creator god for eternal rest. Based on their ancestry, or at the discretion of the DM, an elf may see scenes of their past lives when in trance. A DM may lead up to discovering these ruins by including vague details about an elven character’s past life, lived in this castle, before destruction and then reincarnation. Upon seeing the fountain, these memories flood back into the elf’s mind, and they understand their connection to this location.

Scenario 3

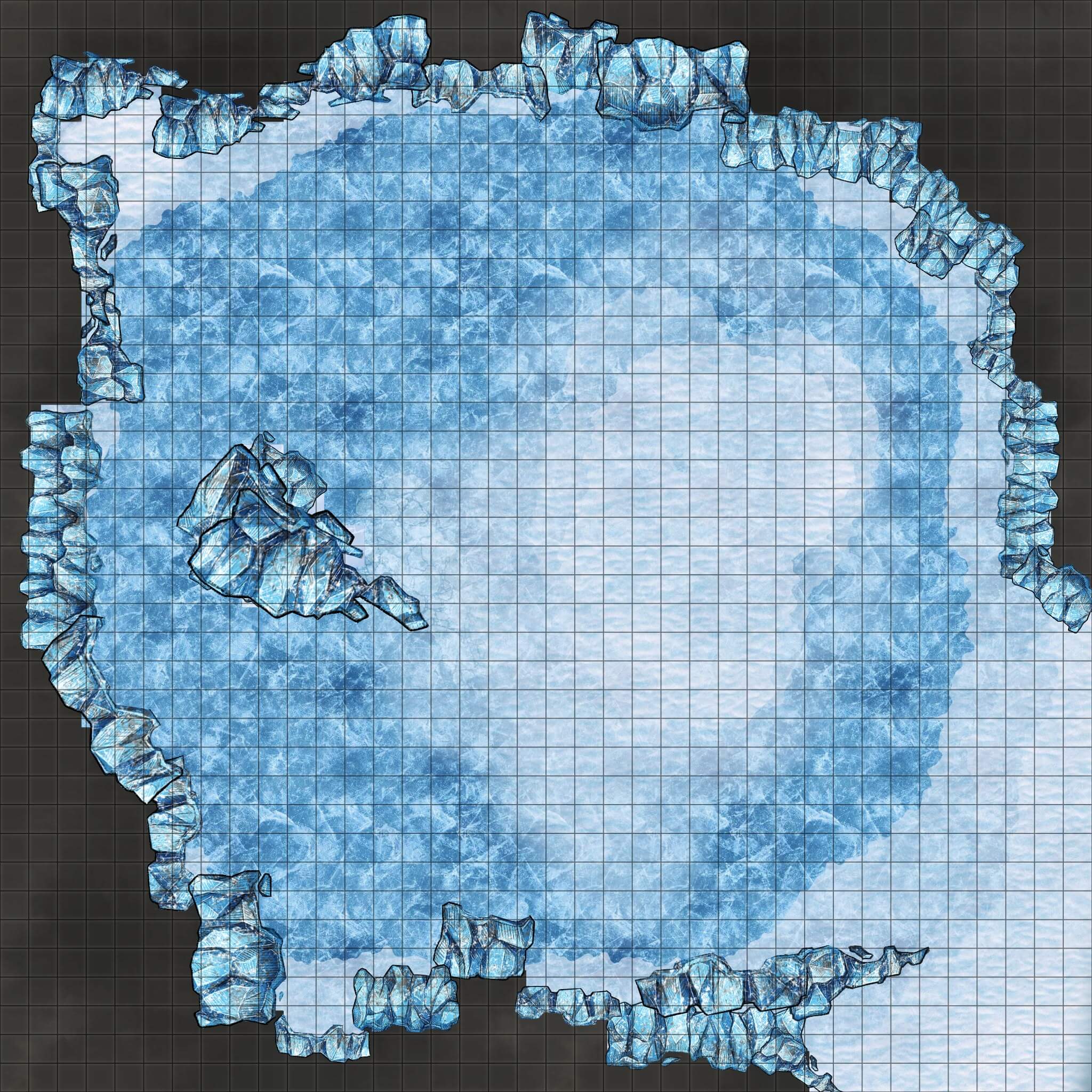

Players explore a colossal ice cave and discover the lair of an Adult White Dragon (CR 13).

Simple Battlefield:

This battlefield already has some exciting elements: difficult icy terrain, jutting walls for cover and possible under-ice pools of water. All of these elements work well with the lair environment of a white dragon, but players can’t really use them to their advantage.

Reading the description of the adult white dragon, we learn some of the elements that make this fight tricky:

“A white dragon rests on high ice shelves and cliffs in its lair, the floor around it a treacherous morass of broken ice and stone, hidden pits, and slippery slopes. As foes struggle to move toward it, the dragon flies from perch to perch and destroys them with its freezing breath.”

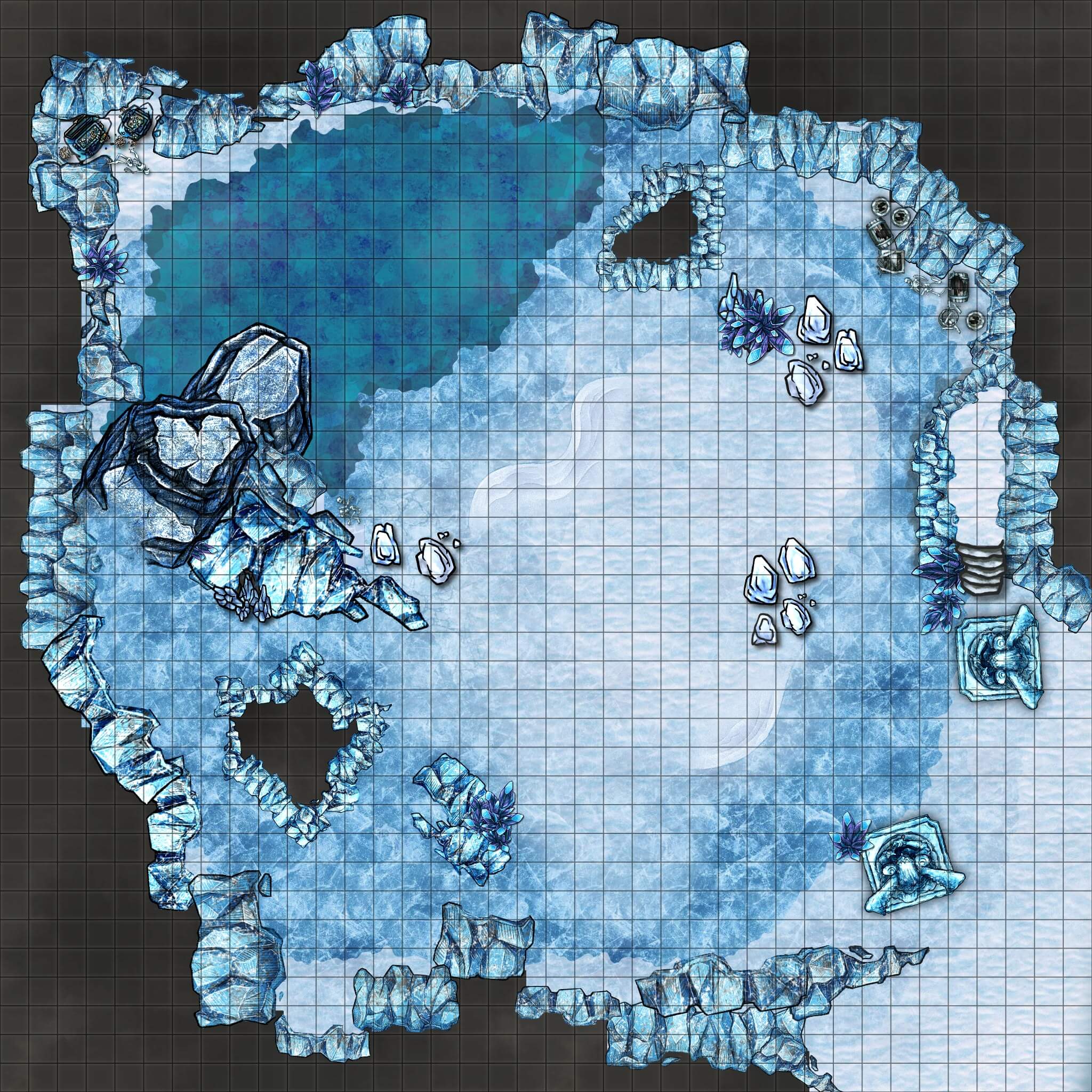

Step 1 – Interactive Environment

While there are some walls they can duck behind, a battle against an adult white dragon is going to be difficult and long. Between Cold Breath, Frightful Presence, and any additional tactics provided by the DM, players will need places to take cover, lest they suffer extreme damage.

When creating the map, remember that white dragons can fly and have no need for ground travel, unless the ceiling is too low. However, in its own lair, space should not be an issue. In this new map, I’ve created a few blindspots and places for players to take cover, if at least for a round. There are also multiple levels of height: a rock mountain overlooking the pool of water and a natural raised platform near the entrance statues. When fighting an aerial creature, these levels may be the difference between success and failure.

Additionally, I’ve included snow banks, ice shards, and corpses. Depending on their footwear, players may have an easier time fighting on the snowbanks, but those are the spaces with least cover. Ice shards can indicate spots where icicles hang above, which can be hit to drop by either the players or the dragon for damage. Corpses may indicate places where the dragon has an advantage, such as from its perch.

Step 2 – Unexpected Abilities and Tactics:

The white dragon has many lair options and legendary actions to choose from in its built-in stats, so think about the specifics of your map for additional tactics. As mentioned, the dragon could cause large icicles to fall from the cavern ceiling (dexterity ST, DC 14, 2d6 piercing damage). The dragon may also have something lurking in the icy water, ready to snatch a player who seeks refuge there.

It would not be unusual for an ice dragon to have small companions, like ice mephits or kobolds.

Step 3 – Add Something Meaningful to Players:

Besides the untold treasures within the frozen chests beyond the lake, players most definitely would need a reason for this quest to the white dragon’s lair. What are they seeking? How does it relate to them individually?

Unless the dragon specifically ties into a single player’s backstory, I would focus on the macro storytelling of the campaign. What goals are furthered by defeating or subduing the dragon? What treasures could they discover here that tell a story or solve a mystery?

Conclusion

If you have players who, like me, find most combat a lackluster grind, consider these three steps to improve your combat. Do any of these tips resonate with you? What have you incorporated to make combat more engaging? Let us know in the comments!

3 Steps to Improve TTRPG Combat Encounters:

- Incorporate interactive map elements

- Give your monsters unexpected abilities and tactics

- Add something meaningful to the players or story